#ArtIsEverywhere: The Loud Silence Of Pictures (My NDTV-Mojarto Column)

Dhiraj Singh | 30 Sep 2019

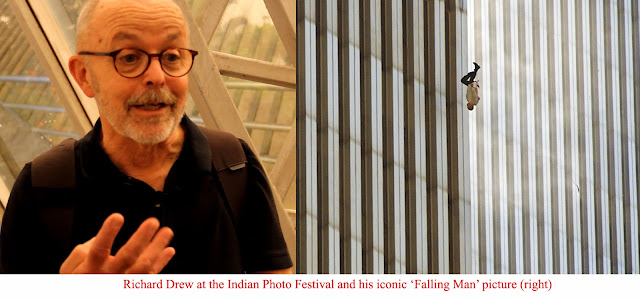

RICHARD DREW IS ALSO KNOWN as the ‘Falling Man Photographer’. It’s not as if he’s not taken other photos. But his ‘Falling Man’ picture has been his most iconic. It was Esquire magazine that gave the picture its descriptive/metaphoric title through a 7000-word piece on the psychology behind its appeal. It was after all a picture that gave a human face to an apocalyptic event.

In the months and days following 9/11 Drew’s ‘Falling Man’ caught the fancy of political cartoonists, artists and even Lego, the toy company. A tarot lady saw a wider Illuminati conspiracy in it because she felt the image represented the ‘Hanged Man’ tarot card. Writer Don Delillo too borrowed the imagery for a novel that he also called ‘Falling Man’. The book had a character—a performance artist—who suspended himself upside-down in different parts of New York to relive the tragedy. Years later singer Elton John would buy the ‘Falling Man’ picture to add it to his art collection.

There is no doubt that some of the best art in the world is the product of outrage. Like ‘Guernica’ that Picasso painted in response to the bombing of civilians. Drew’s picture too has that quality. Of a work that is so steeped in meaning, metaphor and symbolism that it is difficult to get it out of your head. I met Richard Drew recently at the Indian Photo Festival in Hyderabad where his works are also showing. I was curious to find out how he, the image maker, saw this fascination people had for his work. “I am still awed by how people look at the ‘Falling Man’,” he told me. He was surprised to see some Australian newspapers and TV channels talk about it this year which wasn’t even a milestone anniversary year. And see Donald Trump Jr. post it on Instagram. What he left unanswered though was how the picture affected him. The answer to that I got from Margaret Bourke-White’s writings about taking pictures during World War II. “The blindness lasts as long as it is needed,” she wrote, “while I am actually operating the camera. Days later, when I developed the negatives, I was surprised to find that I could not bring myself to look at the films. I had to have someone else handle and sort them for me.”

Sigmund Freud used the metaphor of the camera to explain the unconscious. Like an undeveloped photograph is contained in the camera so were traumatic events contained in the unconscious mind till they could be developed into a narrative. Which is perhaps why photographers feel the urgency to get stories out of their systems.

French photographer Marylise Vigneau’s pictures too have that quality of freeing the unconscious. One of her pictures was powerful enough to become the standard-bearer of this year’s Indian Photo Festival even though its Founder-Director Aquin Mathews says the fest is designed not to have a theme. Vigneau’s series is about her impressions of Pakistan as seen through the eyes of those living there. She foregrounds her pictures in ‘Article 19’ of Pakistan’s constitution that promises freedom of speech and expression but under ‘reasonable restrictions’. These restrictions though unlisted often take the form of witch-hunts by ‘non-state actors’ against minorities, intellectuals, dissidents, journalists or anybody else not found living life under the ‘Hudood’ laws that criminalize rape victims, pre-marital and same-sex relations among other things. All of Vigneau’s subjects are called ‘Noor’ or ‘light’ as they point towards the fissures in Pakistani society through which the rays of individual expression manage to leak out. Her protagonists are as varied as her portraits of them. Each ‘Noor’ represents a different kind of repression. There is an Ahmadi woman, a gay man, an atheist, a Kathak dancer, an activist and even a dog: all outlaws in a society that is obsessively competitive about religion.

Since this year also saw National Geographic partner with the Indian Photo Festival there were works from NatGeo’s own treasury of images that became part of the show in Hyderabad. These included George Steinmetz’s phenomenal ‘Big Food’ series. National Geographic had asked Steinmetz to explore what industrialized food production meant for the environment. So, he went clicking farms, fishponds and dairies in China, Brazil, Japan and the US to find something new to say. And he did. His aerial pictures—which he takes from a motorized paraglider—give us a staggering peek into our present and future as he shows how entire ecosystems have been pressed into the service of a growing human population. What also sets his work apart from any such similar project is his ability to make pictures that are loud and silent at the same time.

Dhiraj Singh is a well-known journalist, writer, TV personality and artist who has shown his abstract paintings and X-Ray works in India and abroad. More about him can be found at www.dhirajsingh.co.in

Article link on NDTV-Mojarto is HERE

Comments

Post a Comment